The Indus Male Torso Is Typical of Indian Art in Its

Sculpture in the Indian subcontinent, partly because of the climate of the Indian subcontinent makes the long-term survival of organic materials difficult, substantially consists of sculpture of stone, metal or terracotta. It is clear at that place was a great deal of painting, and sculpture in wood and ivory, during these periods, merely there are only a few survivals. The main Indian religions had all, subsequently hesitant starts, developed the use of religious sculpture by around the start of the Mutual Era, and the employ of stone was becoming increasingly widespread.

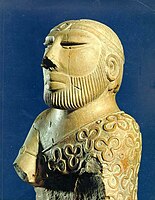

The start known sculpture in the Indian subcontinent is from the Indus Valley civilisation, and a more widespread tradition of small terracotta figures, mostly either of women or animals, which predates information technology.[i] After the collapse of the Indus Valley civilization at that place is little tape of larger sculpture until the Buddhist era, apart from a hoard of copper figures of (somewhat controversially) c. 1500 BCE from Daimabad.[ii] Thus the dandy tradition of Indian monumental sculpture in stone appears to brainstorm relatively late, with the reign of Asoka from 270 to 232 BCE, and the Pillars of Ashoka he erected around India, carrying his edicts and topped by famous sculptures of animals, by and large lions, of which vi survive.[3] Big amounts of figurative sculpture, generally in relief, survive from Early Buddhist pilgrimage stupas, to a higher place all Sanchi; these probably developed out of a tradition using forest that too embraced Hinduism.[4]

During the 2nd to 1st century BCE in far northern India, in the Greco-Buddhist art of Gandhara from what is at present southern Afghanistan and northern Pakistan, sculptures became more than explicit, representing episodes of the Buddha's life and teachings.

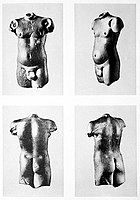

The pink sandstone Hindu, Jain and Buddhist sculptures of Mathura from the 1st to tertiary centuries CE reflected both native Indian traditions and the Western influences received through the Greco-Buddhist art of Gandhara, and effectively established the basis for subsequent Indian religious sculpture.[4] The style was developed and diffused through most of India nether the Gupta Empire (c. 320–550) which remains a "classical" menstruation for Indian sculpture, roofing the earlier Ellora Caves,[five] though the Elephanta Caves are probably slightly later.[6] Later large scale sculpture remains almost exclusively religious, and generally rather bourgeois, oft reverting to simple frontal standing poses for deities, though the bellboy spirits such as apsaras and yakshi oftentimes have sensuously curving poses. Carving is frequently highly detailed, with an intricate backing behind the master effigy in high relief. The celebrated bronzes of the Chola dynasty (c. 850–1250) from southward Bharat, many designed to exist carried in processions, include the iconic form of Shiva every bit Nataraja,[vii] with the massive granite carvings of Mahabalipuram[8] dating from the previous Pallava dynasty.[nine]

Bronze age sculpture [edit]

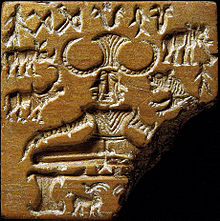

The first known sculpture in the Indian subcontinent is from the Indus Valley civilization (3300–1700 BCE). These include the famous small bronze Dancing Girl. However such figures in bronze and stone are rare and greatly outnumbered past pottery figurines and stone seals, often of animals or deities very finely depicted.[10]

-

-

-

The 2nd Dancing Girl bronze effigy

-

Daimabad Chariot

-

Adult female riding two bulls (bronze), from Kausambi, c. 2000-1750 BCE

Pre-Mauryan art [edit]

Some very early depictions of deities seem to announced in the art of the Indus Valley Civilisation (3300 BCE - 1700 BCE), but the following millennium, congruent with the Vedic period, is devoid of such remains.[11] It has been suggested that the early Vedic religion focused exclusively on the worship of purely "elementary forces of nature by means of elaborate sacrifices", which did not lend themselves hands to anthropomorphological representations.[12]

Terracotta figurine, Mathura, quaternary century BCE

Diverse artefacts may vest to the Copper Hoard Culture (2nd millennium BCE), some of them suggesting anthropomorphological characteristics.[thirteen] Interpretations vary as to the exact signification of these artifacts, or fifty-fifty the civilization and the periodization to which they belonged.[thirteen] Some examples of artistic expression also appear in abstract pottery designs during the Black and reddish ware civilization (1450-1200 BCE) or the Painted Grey Ware civilisation (1200-600 BCE), with finds in a broad expanse.[xiii]

Most of the early finds following this menses represent to what is called the "second flow of urbanization" in the center of the 1st millennium BCE, afterward a gap about a thousand years following the collapse of the Indus Valley Civilization.[xiii] The anthropomorphic depiction of various deities apparently started in the centre of the 1st millennium BCE, possibly every bit a outcome of the influx of foreign stimuli initiated with the Achaemenid conquest of the Indus Valley, and the rise of alternative local faiths challenging Vedism, such equally Buddhism and Jainism and local popular cults.[11] Some rudimentary terracotta artifacts may date to this menstruum, only before the Mauryan era.[14]

Art of the Mauryan period [edit]

The surviving art of the Mauryan Empire which ruled, at to the lowest degree in theory, over most of the Indian subcontinent between 322 and 185 BCE is by and large sculpture. In that location was an purple court-sponsored art patronized by the emperors, especially Ashoka, and and so a "popular" style produced past all others.

The virtually pregnant remains of awe-inspiring Mauryan art include the remains of the royal palace and the city of Pataliputra, a monolithic rail at Sarnath, the Bodhimandala or the altar resting on 4 pillars at Bodhgaya, the stone-cut chaitya-halls in the Barabar Caves near Gaya, the non-edict bearing and edict bearing pillars, the animal sculptures crowning the pillars with animal and botanical reliefs decorating the abaci of the capitals and the front end half of the representation of an elephant carved out in the round from a live stone at Dhauli.[15]

This menstruum marked the appearance of Indian stone sculpture; much previous sculpture was probably in forest and has non survived. The elaborately carved animal capitals surviving on from some Pillars of Ashoka are the best known works, and amidst the finest, above all the Panthera leo Uppercase of Ashoka from Sarnath that is now the National Emblem of Bharat. Coomaraswamy distinguishes between court art and a more than pop art during the Mauryan menstruation. Courtroom art is represented by the pillars and their capitals,[xvi] and surviving popular art by some rock pieces, and many smaller works in terra cotta.

The highly polished surface of court sculpture is often called Mauryan smoothen. Withal this seems not to be entirely reliable as a diagnostic tool for a Mauryan date, as some works from considerably later periods also have information technology. The Didarganj Yakshi, at present nigh ofttimes thought to be from the 2nd century CE, is an example.

-

Masarh panthera leo sculpture

-

Mauryan statue 3rd-2nd century BCE

-

-

Yaksha statue

-

Didarganj Yakshi

Art of the Shunga menses (180-fourscore BCE) [edit]

Terracotta arts executed during pre-Mauryan and Mauryan periods are further refined during Shunga periods and Chandraketugarh sally as an important center for the terra cotta arts of Shunga period. Mathura which has its basis in the pre-Mauryan menstruation too emerges as an important eye for Jain, Hindu and Buddhist art.

-

Bharhut stupa, Shunga horseman

-

Shunga Yakshi

-

Chandraketugarh figurine

-

Male figure, Chandraketugarh, India, 2nd-1st century BCE

-

Bharhut Yavana(Greek) Warrior

Satavahana fine art [edit]

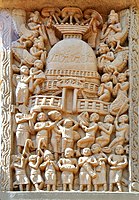

The Satavahana dynasty ruled much of the Deccan and sometimes other areas, including Maharashtra, betwixt well-nigh the 2nd-century BCE and 2nd century CE. They were a Buddhist dynasty, and the almost meaning remains of their sculptural patronage are the Sanchi and Amaravati Stupas,[xviii] forth with a number of rock-cut complexes.

Sanchi stupas were constructed past Emperor Ashoka and after expanded past Shungas and Satavahanas. Major work on decorating the site with Torana gateway and railing was washed by Satavahana Empire.

-

Sanchi gateway

-

Carved reliefs of Sanchi gateway

-

Satavahana relief regarding the metropolis of Kusinagara in the war over the Buddha's relics, South Gate, Stupa no. i, Sanchi

-

Bimbisara with his royal cortege issuing from the city of Rajagriha to visit the Buddha.

-

Foreigners making a dedication to the Great Stupa at Sanchi.

Cave temples [edit]

Between the 2nd century BCE and 2nd century CE nether Satavahanas, several Buddhist caves propped up along the coastal areas of Maharashtra and these cave temples were decorated with Satavahana era sculptures and hence not merely some of the earliest fine art depictions, but evidence of ancient Indian architecture.

-

Kanheri caves statue

Amaravathi art [edit]

The Amaravati school of Buddhist art was one of the iii major Buddhist sculpture centres along with Mathura and Gandhara and flourished under Satavahanas, many limestone sculptures and tablets which once were plastered Buddhist stupas provide a fascinating insight into major early Buddhist school of arts.

-

Head of a lion, from Gateway pillar at the Amaravati Stupa

-

Mara'south assail on the Buddha, second century CE, Amaravati

Early on South Bharat [edit]

Stone sculpture was much after to arrive in South India than the northward, and the earliest period is only represented by the lingam with a standing figure of Shiva in the hamlet of Gudimallam, in the southern tip of Andhra Pradesh. The "mysteriousness" of this "lies in the full absenteeism so far of whatever object in an even remotely similar manner inside many hundreds of miles, and indeed anywhere in S India".[nineteen] Information technology is some 5 ft in height and ane foot thick; the penis is relatively naturalistic, with the glans shown conspicuously. The stone is local, and the style described past Harle equally "Satavahana-related".[19] Information technology is dated to the 3rd century BCE,[20] or 2nd/1st century BCE.[nineteen]

Though the hardness of local granites, the relatively limited penetration of Buddhism and Jainism in the deep south, and a presumed persistent preference for wood have all been proposed as factors in the late development of rock architecture and sculpture in the due south, "the mystery remains".[21] The class of the Gudimallam linga, for case, would be a natural one to evolve in wood, using a straight tree trunk very efficiently, but to say that it did and so is pure speculation in our present land of knowledge. Wooden sculpture, and architecture, has remained common in Kerala, where stone is hard to come by, but this means survivals are very largely limited to the final few centuries.[22]

Kushana art [edit]

Kushan fine art is highlighted by the appearance of all-encompassing Buddhist arts in the form of Mathuras, Gandharan and Amaravathi schools of fine art.

Mathura art [edit]

Mathura art flourished in the ancient city of Mathura and predominantly cerise sandstone has been used in making Buddhist and Jain sculptures.

-

Spotted red sandstone Bodhisattwa, Mathura Art, Kushan Empire, 2d century CE

-

Yakshi Mathura

-

Sibijataka and other Buddhist legends, Mathura fine art, second century CE

Gandharan art [edit]

Greco-Buddhist art is the artistic manifestation of Greco-Buddhism, a cultural syncretism betwixt the Classical Greek culture and Buddhism, which developed over a period of shut to grand years in Key Asia, betwixt the conquests of Alexander the Bang-up in the 4th century BCE, and the Islamic conquests of the 7th century CE. Greco-Buddhist art is characterized by the potent idealistic realism of Hellenistic art and the first representations of the Buddha in human class, which take helped ascertain the artistic (and particularly, sculptural) catechism for Buddhist fine art throughout the Asian continent up to the present. Though dating is uncertain, information technology appears that strongly Hellenistic styles lingered in the Eastward for several centuries subsequently they had declined effectually the Mediterranean, as late as the 5th century CE. Some aspects of Greek art were adopted while others did not spread beyond the Greco-Buddhist area; in particular the standing figure, frequently with a relaxed pose and one leg flexed, and the flying cupids or victories, who became pop across Asia equally apsaras. Greek leaf ornamentation was also influential, with Indian versions of the Corinthian upper-case letter appearing.[27]

Although India had a long sculptural tradition and a mastery of rich iconography, the Buddha was never represented in human class earlier this time, only simply through some of his symbols.[28] This may exist because Gandharan Buddhist sculpture in modern Afghanistan displays Greek and Persian artistic influence. Artistically, the Gandharan school of sculpture is said to have contributed wavy pilus, pall covering both shoulders, shoes and sandals, acanthus foliage decorations, etc.

The origins of Greco-Buddhist art are to be found in the Hellenistic Greco-Bactrian kingdom (250 BCE – 130 BCE), located in today's Afghanistan, from which Hellenistic culture radiated into the Indian subcontinent with the establishment of the small Indo-Greek kingdom (180 BCE-ten BCE). Nether the Indo-Greeks and so the Kushans, the interaction of Greek and Buddhist culture flourished in the area of Gandhara, in today's northern Pakistan, earlier spreading further into India, influencing the art of Mathura, and so the Hindu fine art of the Gupta empire, which was to extend to the rest of S-Due east Asia. The influence of Greco-Buddhist art also spread north towards Fundamental Asia, strongly affecting the art of the Tarim Bowl and the Dunhuang Caves, and ultimately the sculpted figure in China, Korea, and Japan.[29]

-

Stucco Buddha head from Hadda, Transitional islamic state of afghanistan, 3rd–fourth centuries. This was painted.

-

Gupta catamenia [edit]

Gupta fine art is the style of art, surviving well-nigh entirely as sculpture, adult under the Gupta Empire, which ruled about of northern India, with its peak between virtually 300 and 480 CE, surviving in much reduced form until c. 550. The Gupta catamenia is more often than not regarded as a classic summit and gilded historic period of Northward Indian fine art for all the major religious groups.[30] Although painting was evidently widespread, the surviving works are nigh all religious sculpture. The period saw the emergence of the iconic carved rock deity in Hindu art, while the production of the Buddha-figure and Jain tirthankara figures continued to expand, the latter oftentimes on a very large scale. The traditional principal heart of sculpture was Mathura, which continued to flourish, with the art of Gandhara, the heart of Greco-Buddhist art just beyond the northern edge of Gupta territory, continuing to exert influence. Other centres emerged during the period, especially at Sarnath. Both Mathura and Sarnath exported sculpture to other parts of northern India.

It is customary to include under "Gupta art" works from areas in northward and central India that were not actually under Gupta control, in item art produced under the Vakataka dynasty who ruled the Deccan c. 250–500.[31] Their region independent very of import sites such as the Ajanta Caves and Elephanta Caves, both mostly created in this period, and the Ellora Caves which were probably begun and then. Also, although the empire lost its western territories past about 500, the artistic mode continued to be used beyond most of northern India until about 550,[32] and arguably effectually 650.[33] It was then followed by the "Post-Gupta" menstruum, with (to a reducing extent over time) many similar characteristics; Harle ends this effectually 950.[34] Iii main schools of Gupta sculpture are often recognised, based in Mathura, Varanasi/Sarnath and to a bottom extent Nalanda.[35] The distinctively unlike stones used for sculptures exported from the main centres described beneath aids identification greatly.[36]

Both Buddhist and Hindu sculpture concentrate on large, often near life-size, figures of the major deities, respectively Buddha, Vishnu and Shiva. The dynasty had a partiality to Vishnu, who now features more prominently, where the Kushan imperial family unit more often than not had preferred Shiva. Pocket-size figures such as yakshi, which had been very prominent in preceding periods, are at present smaller and less frequently represented, and the crowded scenes illustrating Jataka tales of the Buddha's previous lives are rare.[37] When scenes include one of the major figures and other less of import ones, at that place is a cracking departure in scale, with the major figures many times larger. This is also the case in representations of incidents from the Buddha's life, which earlier had showed all the figures on the same scale.[38]

The lingam was the central murti in almost temples. Some new figures announced, including personifications of the Ganges and Yamuna rivers, not withal worshipped, but placed on either side of entrances; these were "the two great rivers encompassing the Gupta heartland".[39] The main bodhisattva appear prominently in sculpture for the first time,[40] as in the paintings at Ajanta. Buddhist, Hindu and Jain sculpture all evidence the same way,[41] and there is a "growing likeness of course" between figures from the different religions, which continued afterward the Gupta period.[32]

The Indian stylistic tradition of representing the body equally a series of "smooth, very simplified planes" is continued, though poses, specially in the many continuing figures, are subtly tilted and varied, in dissimilarity to the "columnar rigidity" of before figures.[42] The detail of facial parts, hair, headgear, jewellery and the haloes behind figures are carved very precisely, giving a pleasing dissimilarity with the accent on wide swelling masses in the body.[43] Deities of all the religions are shown in a calm and majestic meditative manner; "perhaps it is this all-pervading inwardness that accounts for the unequalled Gupta and mail-Gupta ability to communicate higher spiritual states".[32]

-

Buddha from Sarnath, 5–6th century CE

Medieval, c. 600 onwards [edit]

Pala and Sena empires [edit]

The Pala Empire ruled a large area in northward and eastward India between the 8th and 12th centuries CE, mostly later inherited by the Sena Empire. During this time, the mode of sculpture inverse from "Post-Gupta" to a distinctive style that was widely influential in other areas and later centuries. Deity figures became more rigid in posture, very often standing with directly legs close together, and figures were oftentimes heavily loaded with jewellery; they very often accept multiple artillery, a convention assuasive them to concord many attributes and display mudras. The typical form for temple images is a slab with a main figure, rather over half life-size, in very loftier relief, surrounded by smaller bellboy figures, who might have freer tribhanga poses. Critics have constitute the way disposed towards over-elaboration. The quality of the etching is generally very loftier, with crisp, precise item. In e India, facial features tend to become sharp.[44]

Though the Pala monarchs are recorded as patronizing religious establishments in a general sense, their patronage of whatever specific work of art cannot be documented past the surviving evidence, which is mostly inscriptions.[45] Nevertheless, there are much larger numbers of images that are dated, every bit compared to other Indian regions and periods, helping profoundly the reconstruction of stylistic development.[46]

Much larger numbers of smaller bronze groups of similar limerick have survived than from previous periods. Probably the numbers produced were increasing. These were mostly made for domestic shrines of the well-off, and from monasteries. Gradually, Hindu figures come to outnumber Buddhist ones, reflecting the final decline of Indian Buddhism, fifty-fifty in east India, its final stronghold.[47]

Temples of Khajuraho [edit]

The temples of Khajuraho, a circuitous of Hindu and Jain temples, were constructed from the ninth to the 11th centuries by the Chandela dynasty. They are considered one of the best examples of Indian art and architecture.[48]

The temples have a rich display of intricately carved sculptures. While they are famous for their erotic sculptures, sexual themes cover less than a tenth of the temple sculpture. The sculptures draw various aspects the everyday life, mythical stories as well as symbolic display of diverse secular and spiritual values of import in Hindu tradition.[48]

Dynasties of Due south India [edit]

Later on the Gudimallam lingam (see to a higher place), the primeval dynasty of southern India to leave stone sculpture on a large calibration was the long-lasting Pallava dynasty which ruled much of s-east India between 275 and 897, although the major sculptural projects come up from the after function of the period. A number of significant Hindu temples survive, with rich sculptural decoration. Initially these tend to exist stone-cut, every bit are virtually of the Group of Monuments at Mahabalipuram (7th and 8th centuries), perhaps the best-known examples of Pallava art and compages Many of these exploit natural outcrops of rock, which are carved away on all sides until a building is left. Others, like the Shore Temple, are constructed in the usual way, and others cut into a rock face similar almost other rock-cut architecture. The Descent of the Ganges at Mahabalipuram, is "the largest and most elaborate sculptural limerick in Republic of india",[49] a relief carved on a near-vertical rock face some 29 metres (86 feet) wide, featuring hundreds of figures, including a life-size elephant (tardily 7th century).

Other Pallava temples with sculpture surviving in good condition are the Kailasanathar Temple, Vaikunta Perumal Temple and others at Kanchipuram,[50] and the cavern temples at Mamandur. The Pallava fashion in stone reliefs is influenced by the hardness of the stone more often than not used; the relief is less deep and detail such equally jewellery minimized, compared to further northward. The figures are more than slender and "delicately built and project sweetness and unmannered delicacy and refinement";[51] much the same effigy type is continued in Chola sculpture in both stone and statuary. In large narrative panels some of the subjects are distinctively Tamil, such as Korravai (Durga as goddess of victory), and Somaskanda, a seated family group of Shiva, his espoused Parvati and Skanda (Murugan) as a kid.[52]

The "imperial" Chola dynasty begins nearly 850, controlling much of the south, with a irksome decline from about 1150. Large numbers of temples were constructed, which generally suffered far less from Muslim destruction than those further northward. These were heavily decorated with rock relief sculpture, both large narrative panels and unmarried figures, generally in niches on the outside. The Pallava style was broadly connected.

Chola bronzes, the largest by and large almost half life-size, are some of the most iconic and famous sculptures of India, using a similar elegant just powerful mode to the stone pieces. They were created using the lost wax technique. The sculptures were of Shiva in diverse avatars with his consort Parvati, and Vishnu with his consort Lakshmi, among other deities.[53] Even large bronzes had the advantage that they were low-cal enough to be used in processions for festivals.

The most iconic among these is the statuary figure of Shiva as Nataraja, the lord of dance. In his upper right mitt he holds the damaru, the drum of cosmos.[54] In his upper left paw he holds the agni, the flame of destruction. His lower correct manus is lifted in the gesture of the abhaya mudra. His right foot stands upon the demon Apasmara, the embodiment of ignorance.[55]

The Vijayanagara Empire was the last major Hindu empire, amalgam very large temples at Hampi, the uppercase, of which much remains in by and large practiced condition, despite the Mughal army spending a twelvemonth destroying the city after its fall.[56] Temples are often highly decorated, in a manner that farther elaborates the late Chola way, and was influential for afterward South Indian temples. Rows of horses rearing out from columns became a favourite and spectacular device. By the cease of the period hugely expanded multi-storey gopurams had become the most prominent feature of templeas, as they accept remained in the major temples of the due south. The big numbers of figures on these were at present mostly made from brightly painted stucco.

Early Modern period (1206-1858) [edit]

The menses was dominated by Islamic rulers, who not only did not produce figurative sculpture themselves, simply whose armies, especially in the initial conquests, destroyed vast amounts of existing religious sculpture, which considerably discouraged the production of new figures.

All the same, religious sculpture continued, peculiarly in the far south, where the larger temples connected to aggrandize in a rather competitive manner. The tardily medieval southern innovation of towering gopuram gateways continued, and these were covered with large sculptures, in recent centuries mainly in brightly painted stucco. Very large halls were constructed for the large numbers of visitors in temples, sometimes filled with spectacular sculpture, like the famous row of life-size rearing horses at the Ranganathaswamy Temple, Srirangam from the 17th century.

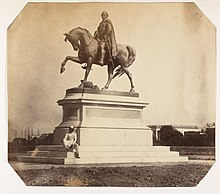

British Colonial period (1858-1947) [edit]

During this period, European styled statues were erected in metropolis squares, as monuments to the British Empire'south ability. Statues of Queen Victoria, George Five, and diverse Governor-Generals of Bharat were erected. Such statues were removed from public places after independence, and placed within museums. However, some still stand at their original location, such equally Statue of Queen Victoria, Bangalore.

Post-independence (1947 - present) [edit]

Modern Indian sculptors include D.P Roy Choudhury, Ramkinkar Baij, Pilloo Pochkhanawala, Mrinalini Mukherjee, Adi Davierwala, Sankho Chaudhuri and Chintamoni Kar.[57] The National Gallery of modern Fine art has a large collection of modern Indian sculpture.[57] Contemporary Indian sculptors include Sudarshan Shetty, Ranjini Shettar, Anita Dube and Rajeshree Goody.

Gallery [edit]

-

Jain chaumukha sculpture, 1st century CE

-

'A Jain Family Group' sculpture, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 6th century

-

13th century Ganesha statue

-

Stone Inscription at ASI Museum, Amaravathi

-

Secular scenes

-

Statue of Suparshvanatha from c. 900 C.E.

-

Seated Ganesha, sandstone sculpture from Rajasthan, 9th century

-

-

Marble Sculpture of female yakshi in typical curving pose, c. 1450, Rajasthan

-

See also [edit]

Notes [edit]

- ^ Blurton, 22

- ^ Harle, 17–xx

- ^ Harle, 22–24

- ^ a b Harle, 26–38

- ^ Harle, 87; his Part ii covers the menstruum

- ^ Harle, 124

- ^ Harle, 301-310, 325-327

- ^ "Group of Monuments at Mahabalipuram". UNESCO World Heritage Eye . Retrieved 2019-02-xx .

- ^ Harle, 276–284

- ^ "Due south Asian arts - Visual arts of Bharat and Sri Lanka (Ceylon)". Encyclopedia Britannica . Retrieved 2019-02-xx .

- ^ a b Paul, Pran Gopal; Paul, Debjani (1989). "Brahmanical Imagery in the Kuṣāṇa Art of Mathurā: Tradition and Innovations". East and W. 39 (i/4): 111–143, peculiarly 112–114, 115, 125. JSTOR 29756891.

- ^ Paul, Pran Gopal; Paul, Debjani (1989). "Brahmanical Imagery in the Kuṣāṇa Art of Mathurā: Tradition and Innovations". East and West. 39 (1/4): 111–143. ISSN 0012-8376. JSTOR 29756891.

- ^ a b c d Shaw, Ian; Jameson, Robert (2008). A Lexicon of Archæology. John Wiley & Sons. p. 248. ISBN978-0-470-75196-one.

- ^ Gupta, C. C. Das (1951). "Unpublished Ancient Indian Terracottas Preserved in the Musée Guimet, Paris". Artibus Asiae. 14 (four): 283–305. doi:x.2307/3248779. ISSN 0004-3648. JSTOR 3248779.

- ^ Mahajan V.D. (1960, reprint 2007). Aboriginal Bharat, New Delhi: S.Chand, New Delhi, ISBN 81-219-0887-half-dozen, p.348

- ^ Thapar, Romila (2001). Aśoka and the Decline of the Mauryas, New Delhi: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-nineteen-564445-10, pp.267-70

- ^ a b Dated 100 BCE in Fig.88 in Quintanilla, Sonya Rhie (2007). History of Early on Stone Sculpture at Mathura: Ca. 150 BCE - 100 CE. BRILL. p. 368, Fig. 88. ISBN9789004155374.

- ^ Harle, 28, 32-38

- ^ a b c Harle, 271

- ^ Doniger, Wendy (2009). The Hindus: An Alternative History. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 22,23. ISBN9780199593347.

- ^ Harle, 271-272, 272 quoted

- ^ Harle, 342-350; Blurton, 225

- ^ "Seated Buddha with Two Attendants". world wide web.kimbellart.org. Kimbell Art Museum.

- ^ "The Buddhist Triad, from Haryana or Mathura, Twelvemonth four of Kaniska (advertizement 82). Kimbell Fine art Museum, Fort Worth." in Museum (Singapore), Asian Civilisations; Krishnan, Gauri Parimoo (2007). The Divine Within: Art & Living Culture of Republic of india & South asia. Globe Scientific Pub. p. 113. ISBN9789810567057.

- ^ Shut-upwardly image of the inscription of the Kimbell Buddha in Fussman, Gérard (1988). Documents épigraphiques kouchans (V). Buddha et Bodhisattva dans 50'art de Mathura : deux Bodhisattvas inscrits de l'an four et l'an 8. p. 27, planche 2.

- ^ "The Buddha accompanied by Vajrapani, who has the characteristics of the Greek Heracles" Clarification of the same image on the comprehend page in Stoneman, Richard (8 June 2021). The Greek Experience of Republic of india: From Alexander to the Indo-Greeks. Princeton University Printing. p. four. ISBN978-0-691-21747-5. Also "Herakles plant an independent life in India in the guise of Vajrapani, the bearded, gild-wielding companion of the Buddha" in Stoneman, Richard (viii June 2021). The Greek Experience of India: From Alexander to the Indo-Greeks. Princeton University Press. pp. 88–89. ISBN978-0-691-21747-five.

- ^ Boardman, 370–378; Harle, 71–84

- ^ Dehejia, Vidya. "Buddhism and Buddhist Fine art". Metropolitan Museum of Fine art . Retrieved 2019-02-20 .

- ^ Boardman, 370–378; Sickman, 85–90; Paine, 29–30

- ^ Rowland'south affiliate 15 is called "The Aureate Age: The Gupta Catamenia; Harle, 88

- ^ Harle, 118

- ^ a b c Harle, 89

- ^ Rowland, 215

- ^ Harle, 199

- ^ Mookerji, 1, 143

- ^ Harle, 89; Rowland, 216; Mookerji, 143

- ^ Harle, 87–88

- ^ Rowland, 234

- ^ Harle, 87–88, 88 quoted

- ^ Rowland, 235

- ^ Rowland, 232

- ^ Rowland, 233

- ^ Rowland, 230–233, 232 and 233 quoted

- ^ Harle, 212-216; Craven, 170, 172-176; Huntington, generally, and p. 29 on freer attendants.

- ^ Huntington, 31 note 27 (the situation is fiddling different for Gupta monarchs).

- ^ Huntington, 37, and Chapter iii generally

- ^ Harle, 212; Craven, 176

- ^ a b c "Khajuraho Group of Monuments". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 2019-02-14. Retrieved 2019-02-20 .

- ^ Harle, 272

- ^ Michell, 434-437

- ^ Harle, 277-278

- ^ Harle, 276-277

- ^ "Cracking Living Chola Temples". UNESCO Earth Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 2018-12-26. Retrieved 2019-02-21 .

- ^ Smith, David (David James), born 1944 (2002). The Trip the light fantastic of Siva: organized religion, art and poetry in South Bharat. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–2. ISBN978-0521528658. OCLC 53987899.

- ^ "Shiva as Lord of Trip the light fantastic (Nataraja)". Metropolitan Museum of Art . Retrieved 2019-02-20 .

- ^ Rowland, 317

- ^ a b "Modern Sculptures". National Gallery of Modernistic Fine art, New Delhi . Retrieved 2019-02-14 .

References [edit]

- Blurton, T. Richard, Hindu Art, 1994, British Museum Press, ISBN 0 7141 1442 ane

- Boardman, John, ed., The Oxford History of Classical Art, 1993, OUP, ISBN 0198143869

- Craven, Roy C., Indian Art: A Concise History, 1987, Thames & Hudson (Praeger in USA), ISBN 0500201463

- Harle, J. C., The Fine art and Compages of the Indian Subcontinent, 2nd edn. 1994, Yale University Press. (Pelican History of Art), ISBN 0300062176

- Huntington, Susan L. (1984). The "Påala-Sena" Schools of Sculpture. Brill Archive. ISBN90-04-06856-two.

- Michell, George, The Penguin Guide to the Monuments of India, Volume 1: Buddhist, Jain, Hindu, 1990, Penguin Books, ISBN 0140081445

- Mookerji, Radhakumud (1997), The Gupta Empire, Motilal Banarsidass Publ., ISBN 9788120804401, google books

- Paine, Robert Treat, in: Paine, R. T. & Soper A, The Art and Architecture of Japan, 3rd ed 1981, Yale Academy Printing. (Pelican History of Art), ISBN 0140561080

- Rowland, Benjamin, The Art and Architecture of India: Buddhist, Hindu, Jain, 1967 (3rd edn.), Pelican History of Art, Penguin, ISBN 0140561021

- Sickman, Laurence, in: Sickman L & Soper A, The Fine art and Architecture of Mainland china, (Pelican History of Art), tertiary ed 1971, Penguin (now Yale History of Art), LOC 70-125675

Farther reading [edit]

- Lerner, Martin (1984). The flame and the lotus: Indian and Southeast Asian art from the Kronos collections . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN978-0870993749 . Retrieved 2016-03-06 .

- Welch, Stuart Cary (1985). India: art and culture, 1300-1900 . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Fine art. ISBN9780944142134.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sculpture_in_the_Indian_subcontinent

0 Response to "The Indus Male Torso Is Typical of Indian Art in Its"

Post a Comment